Designing to build trust between the unhoused and medical providers

Quick Info

- Project: carepoint vending machine

- Timeline: October 2021 to December 2021

- Group members: Grace Swanson, Kelsen Kitchen, Nguyen Tran, and Rodrigo Tarriba

- Project conducted for: Human-Centered Design Department at the University of Washington

Design Question

How do we foster trust between medical providers and people experiencing homelessness, especially in regard to the COVID-19 vaccine?

Overview

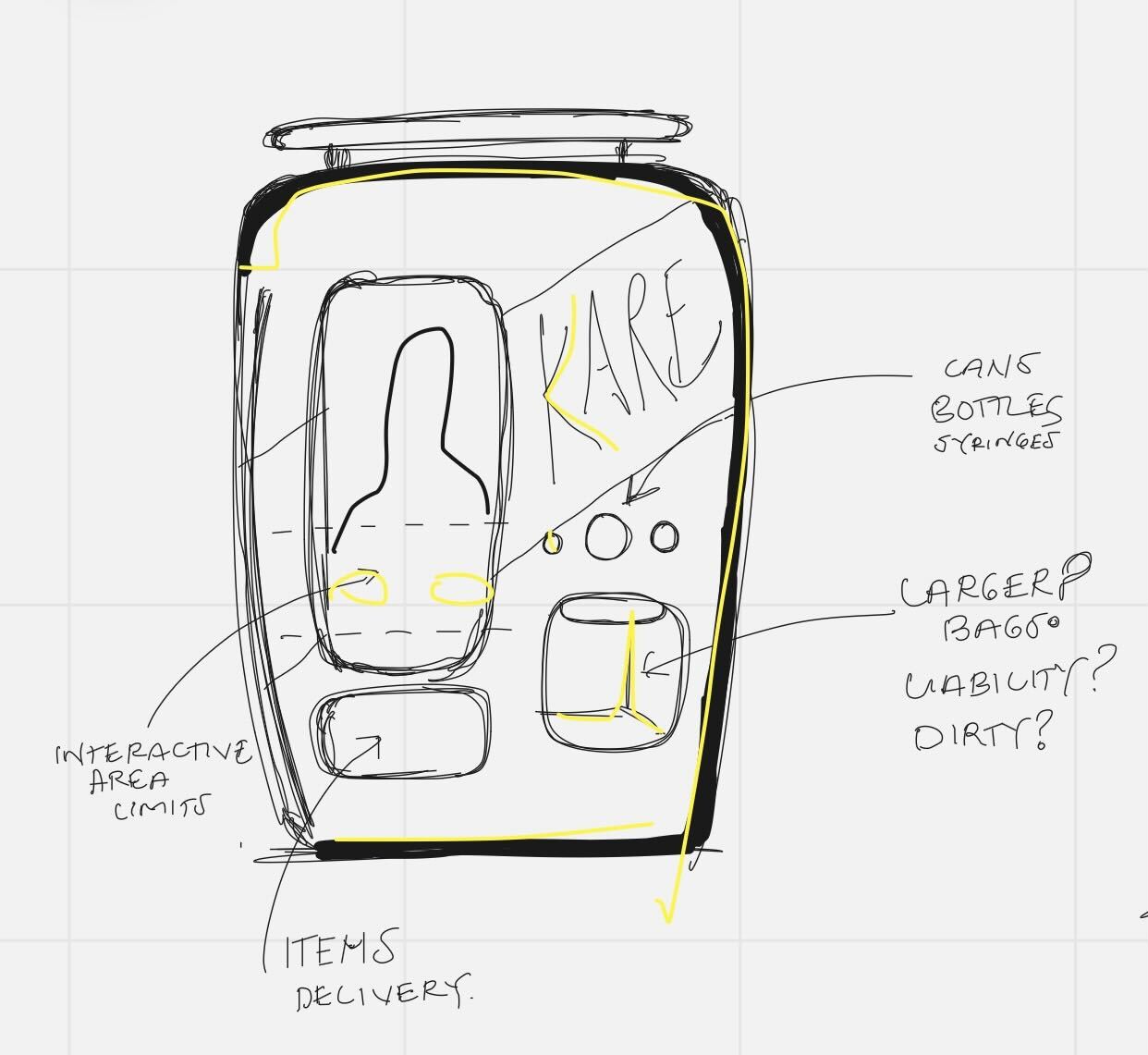

As part of a graduate course in user centered design, I worked on a team that developed a concept called carepoint: a vending machine built in a mobile privacy box that provides essential resources for people experiencing homelessness, specifically related to healthcare. Our solution is meant to be mobile to be moved between encampments, shelters, and other public spaces. It is also meant to be adaptable to the available resources and contributions available.

Here is a link to our high-fidelity screen prototype and here is a link to our video prototype.

As of December 2021, less than 65% of the US population was inoculated against COVID-19. This number was estimated to be even lower amongst people experiencing homelessness (PEH). Based on our research, while many factors contributed to vaccine hesitancy, one major problem to overcome is a general lack of trust between people experiencing homelessness and the US healthcare system as a whole. We set out to develop a design solution to help build and maintain trust between a city's unhoused community and local healthcare providers.

Objectives

- Build trust with PEH by providing their basic needs while respecting their autonomy.

- Allow healthcare providers to have more direct access to the PEH community.

- Create a mutually beneficial environment between PEH and the local community.

Research

The pathway to our final proposal was fraught with challenges. Initially, our team’s scope was broad: we wanted to create a tool to battle misinformation about the COVID-19 vaccine and address vaccine hesitancy. We explored different user groups through our many conversations about how to narrow the scope; one group member suggested we explore vaccine hesitancy among the unhoused population. We used a range of different methods, including:

- User interviews with healthcare workers, social workers and case managers, PEH, and other potential stakeholders

- Secondary research probing relationships and interactions between PEH and healthcare workers

- A 13-question survey to measure people’s experience and opinion on vaccine hesitancy in the unhoused population (aimed at medical providers and other individuals who worked with PEH)

What We Learned

We learned that PEH don’t necessarily mistrust the COVID-19 vaccine, but they mistrust the healthcare system overall.

Our most critical research finding confirmed a general mistrust in the healthcare system by PEH. On a scale from 1 to 10, with one being very uncommon and ten being very common, our survey respondents reported vaccine hesitancy is common in the unhoused population (Mean = 7.04).

The healthcare workers, social workers, and case managers mentioned that PEHs have a lack of trust toward medical providers. This was a critical finding because our field interviews with the unhoused population did not reveal this mistrust. The PEH we interviewed expressed trust in the COVID-19 vaccine, which could indicate that the PEH generally distrust the medical system as a whole, not particularly the COVID-19 vaccine. Another interviewee reiterated that there has to be a warm and respectful relationship between healthcare providers and PEHs in order to see successful vaccination outcomes.

Many PEHs had bad past experiences with healthcare providers. Perhaps not surprisingly, women experiencing/having experienced homelessness describe a loss of dignity in encounters with healthcare services. They also expressed that healthcare services could also offer respite, rest, and sanctuary at a time when they needed them most.

Additionally, the intersectionality between homelessness and groups who were historically mistreated by the healthcare system, such as people of color, contributes to distrust.

Several of our research methods revealed that one-on-one conversations are an effective method to encourage vaccination. Creating a human connection between a healthcare provider and PEH is crucial.

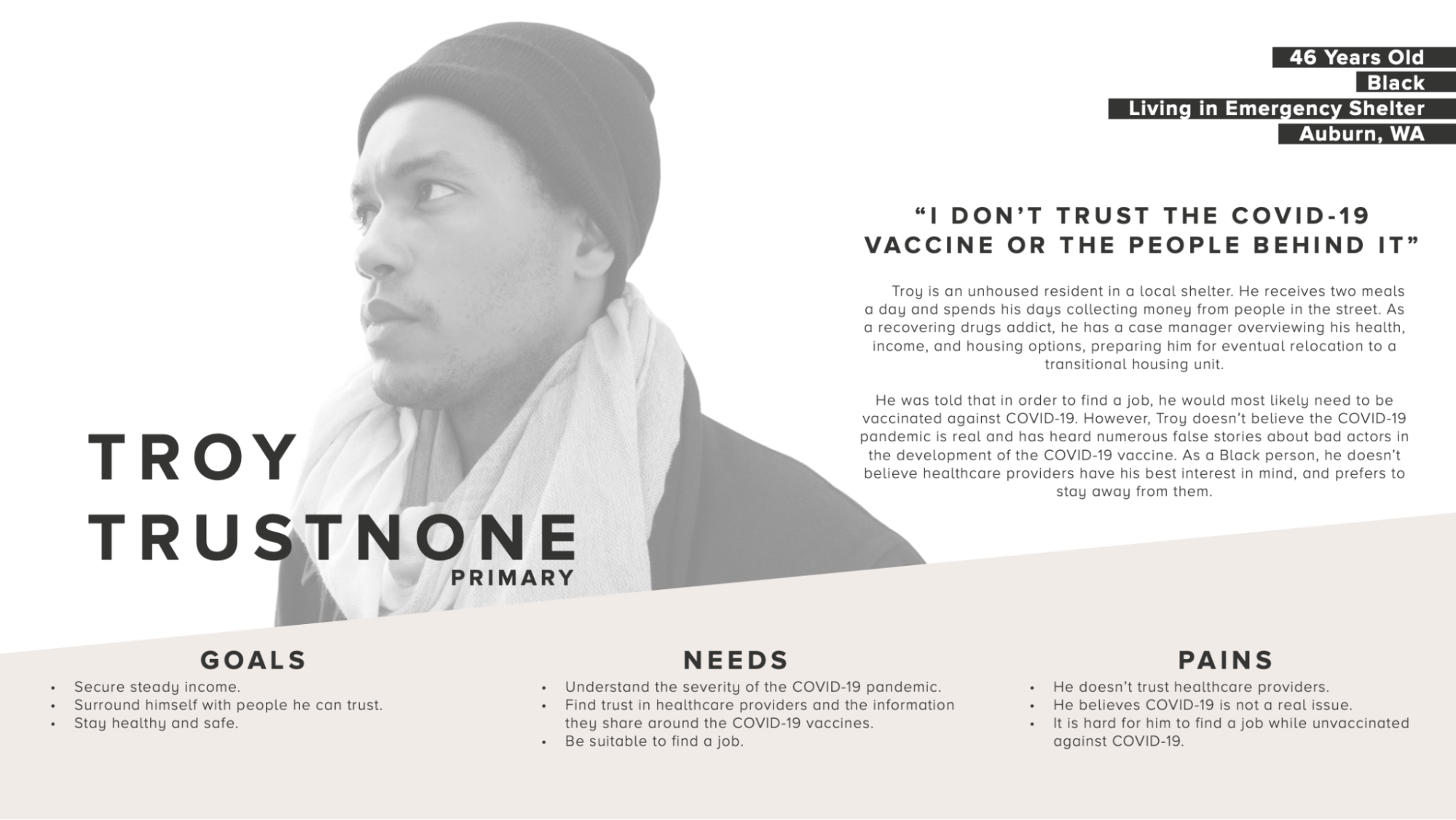

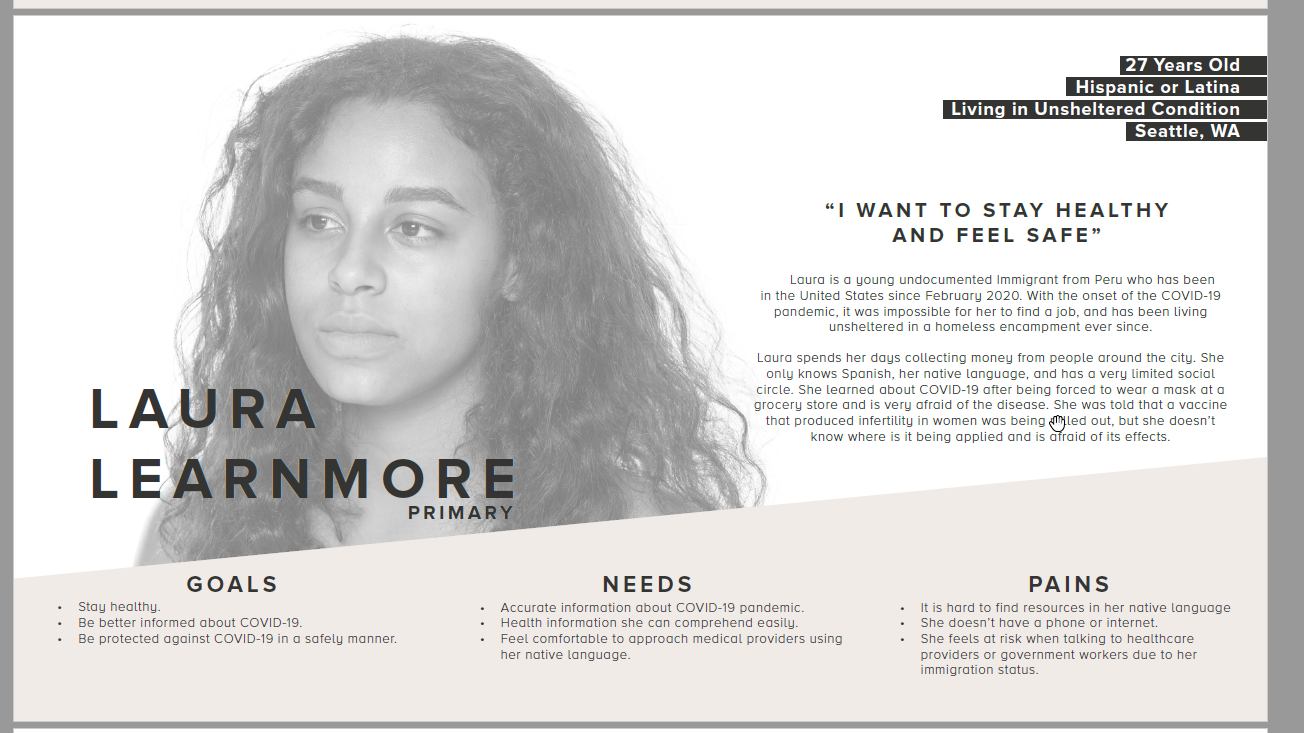

Based on our initial research, we came up with the following personas:

These personas helped us identify our users’ needs and narrow the scope of our user base. We used these personas to inform our future design decisions.

Pivoting

At this point in our journey, we decided to focus on building trust and create an artifact that benefited PEH, healthcare professionals, and local communities. COVID-19 remained a component in our design, but was no longer the primary focus.

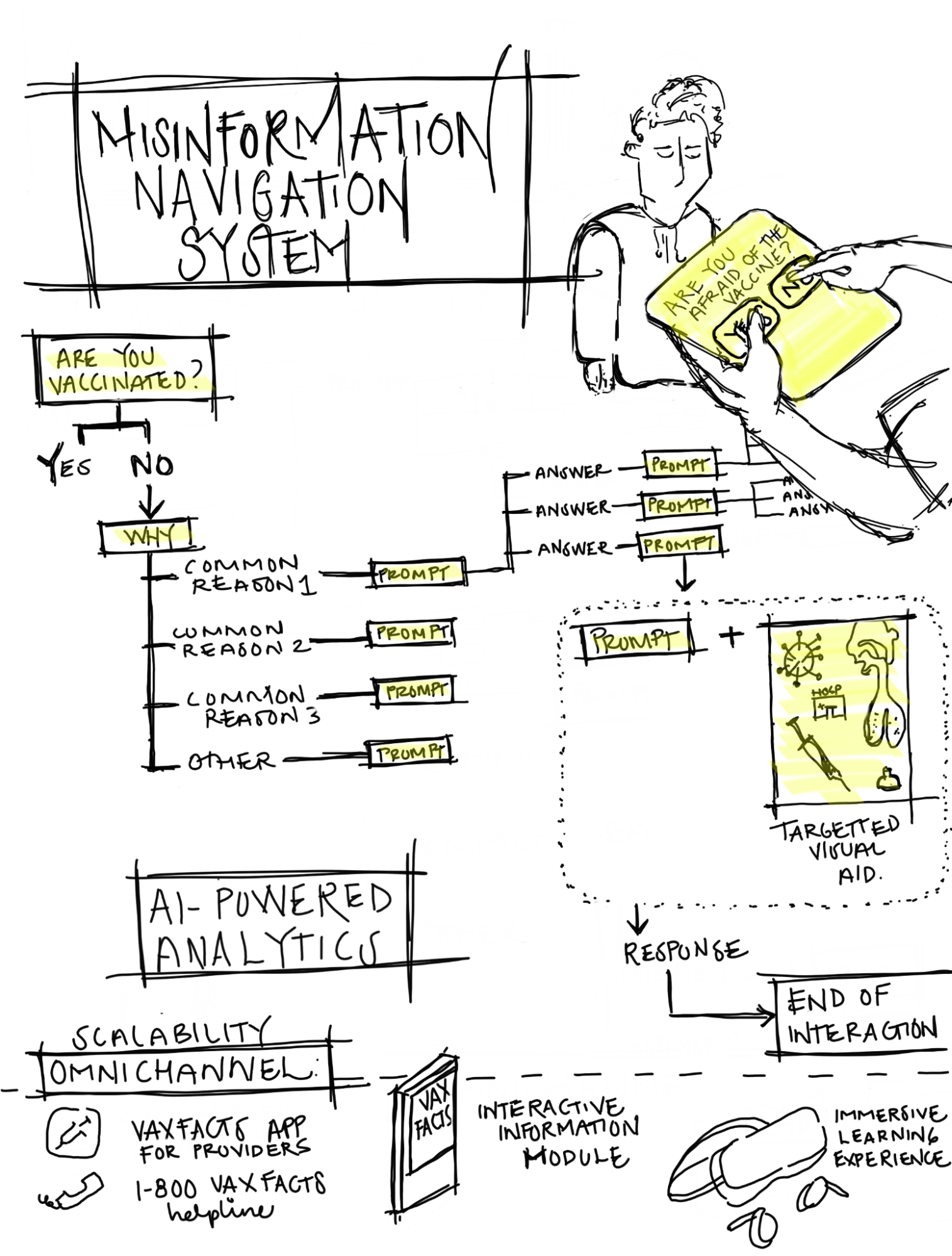

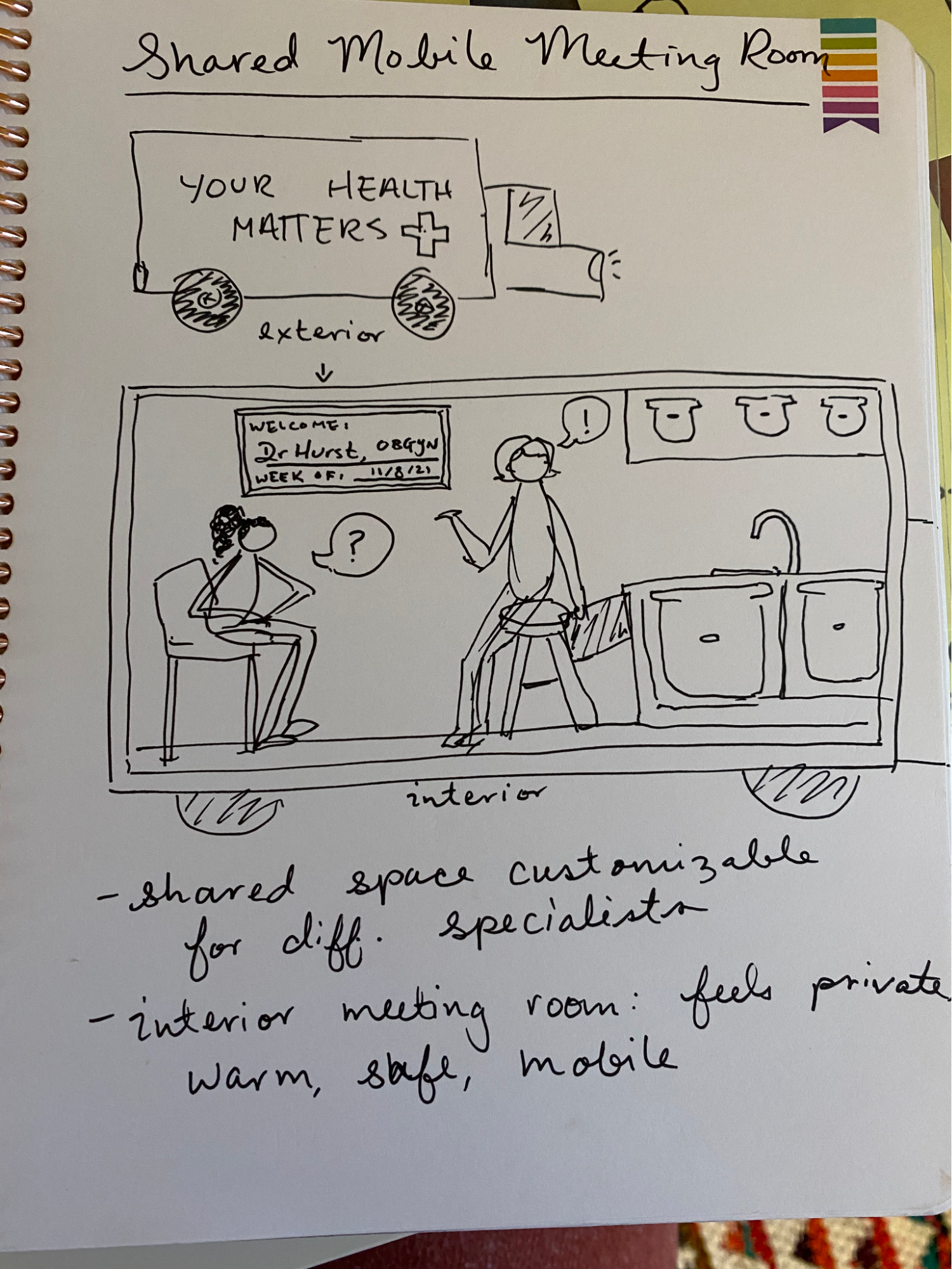

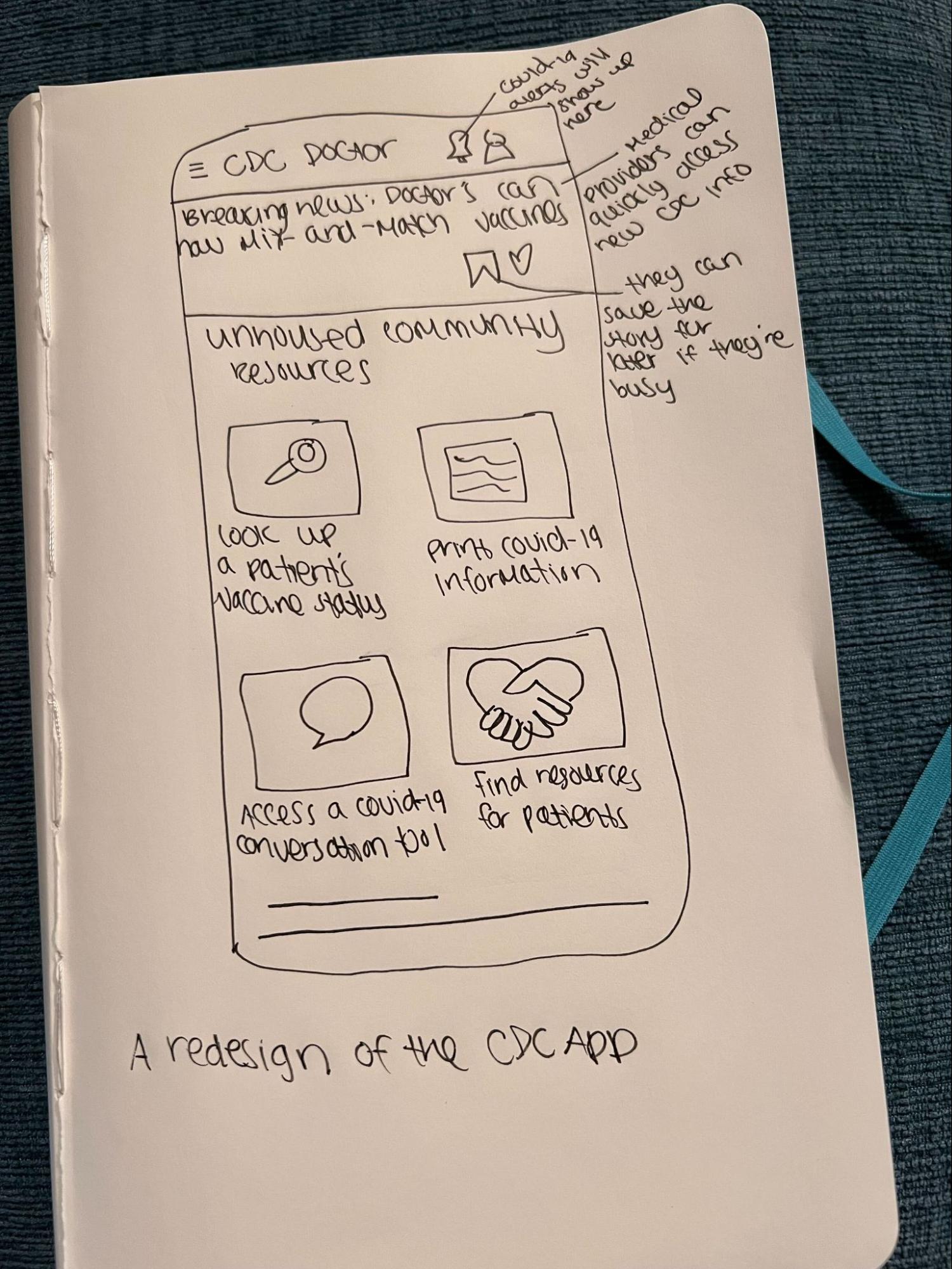

From our sketching brainstorming sessions, we arrived at three initial designs:

- A misinformation navigation system (essentially, a flowchart to guide conversations about COVID-19)

- A shared mobile doctors' office

- A redesign of the CDC app for doctors

The sketching exercise helped us break out of our comfort zone and examine the problem and potential solutions in new ways. Finally, we combined elements of the three final ideas into one, which is how we arrived at carepoint, a transportable vending machine.

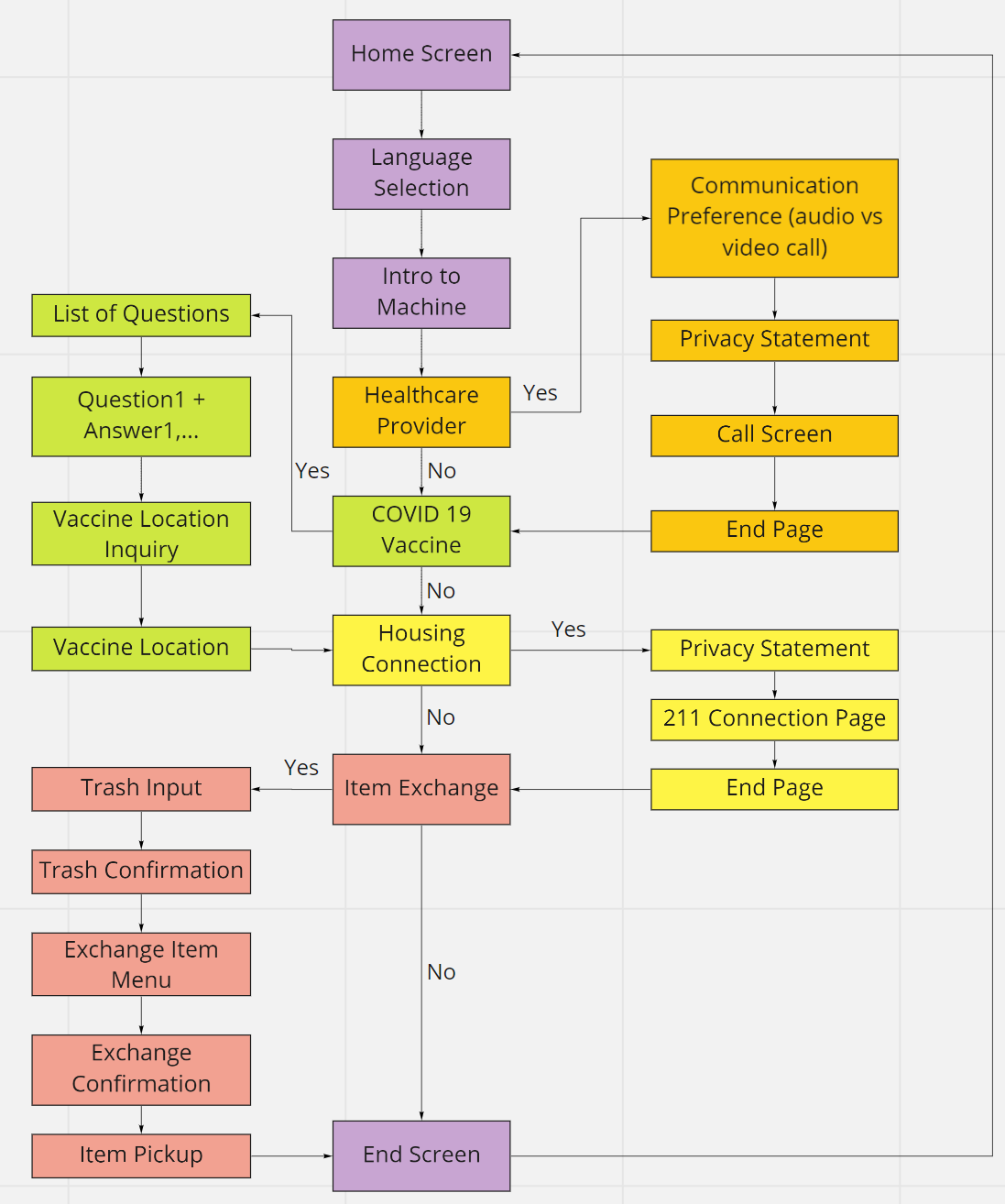

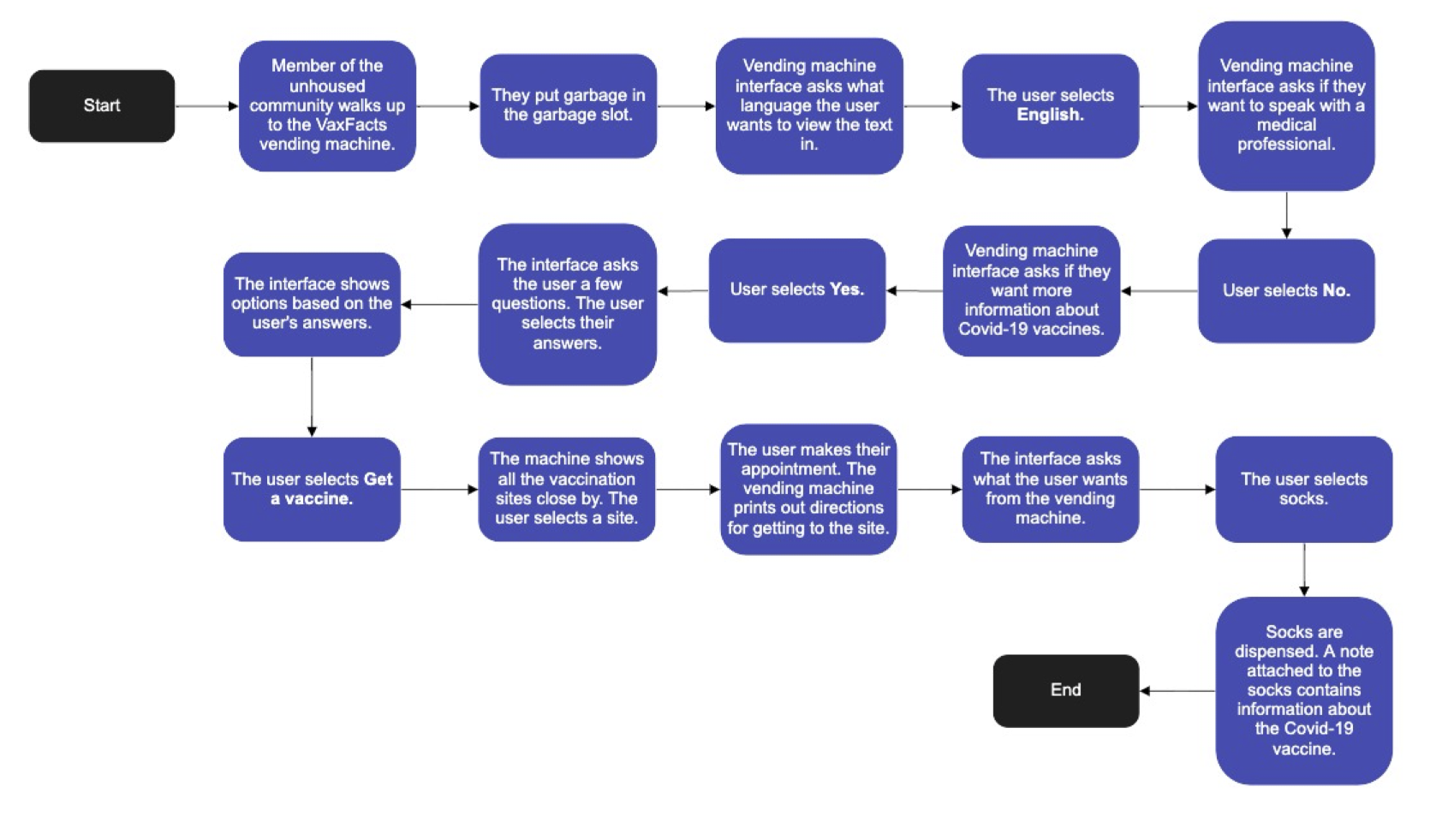

Based on our initial rough prototype, we developed an Information Architecture diagram to map the user flows.

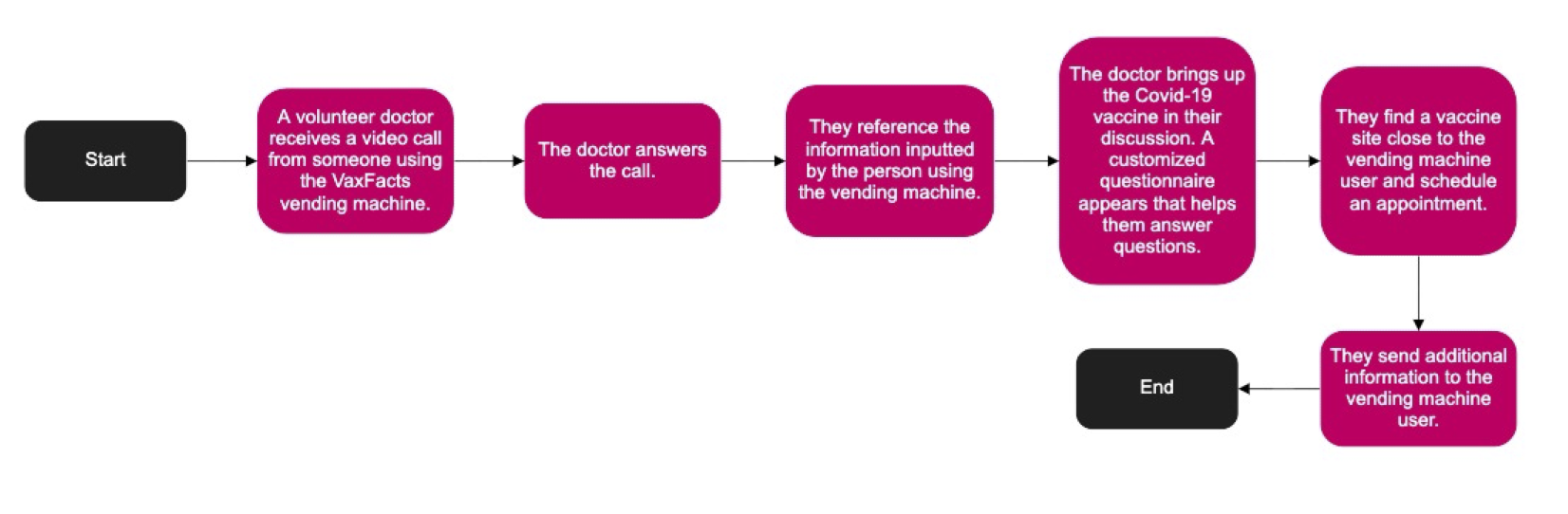

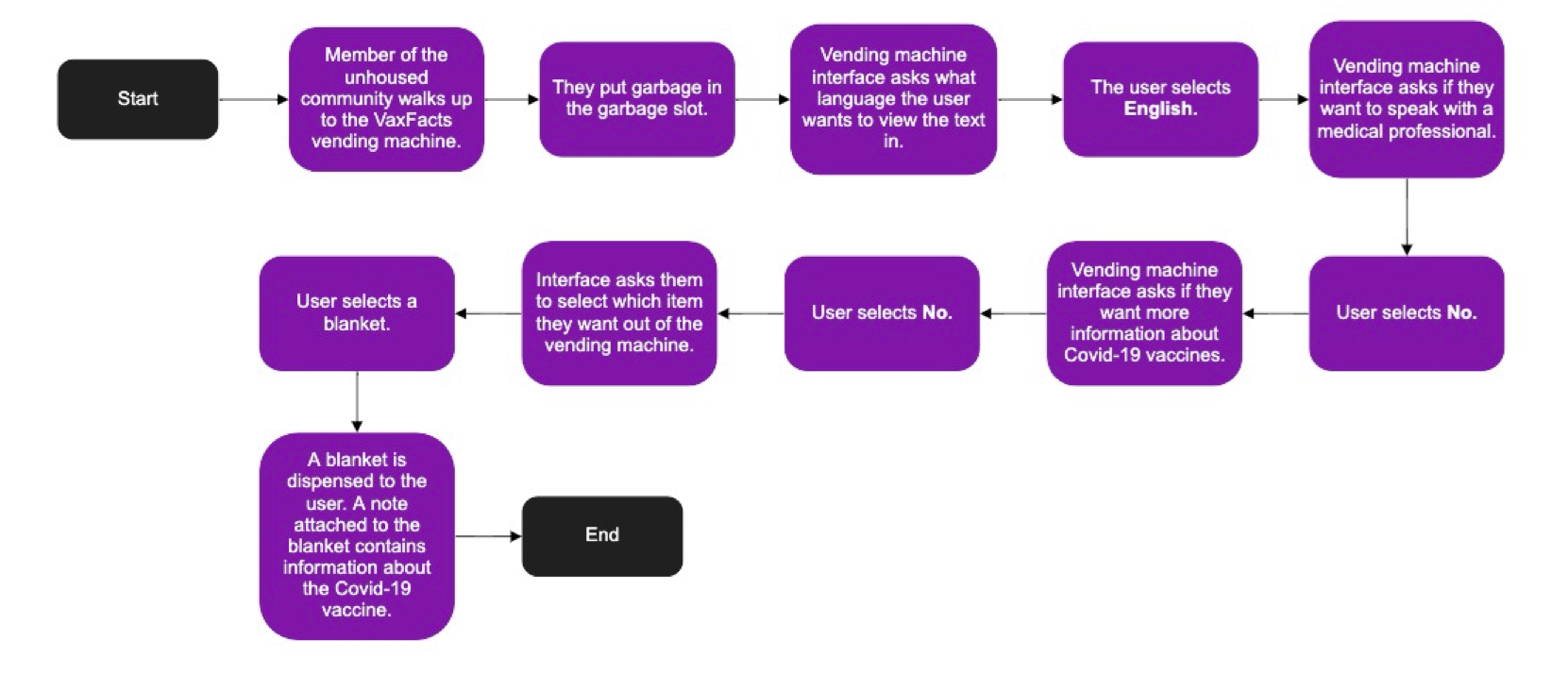

We also developed a few flows that would explore different user interactions with the board. With these flows, we tried to account for different accessibility experiences and included one back-end interaction (a healthcare provider answering a call from carepoint).

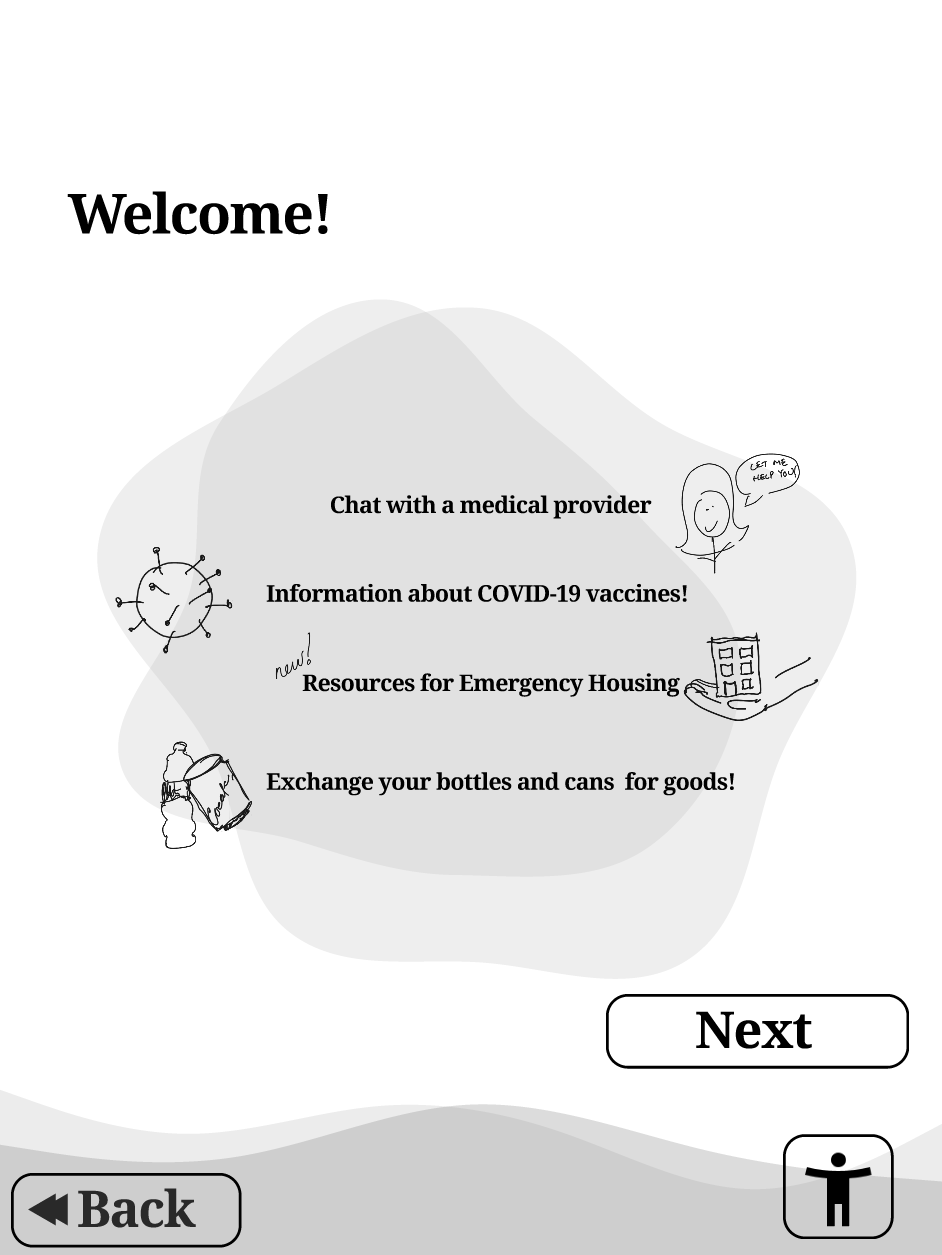

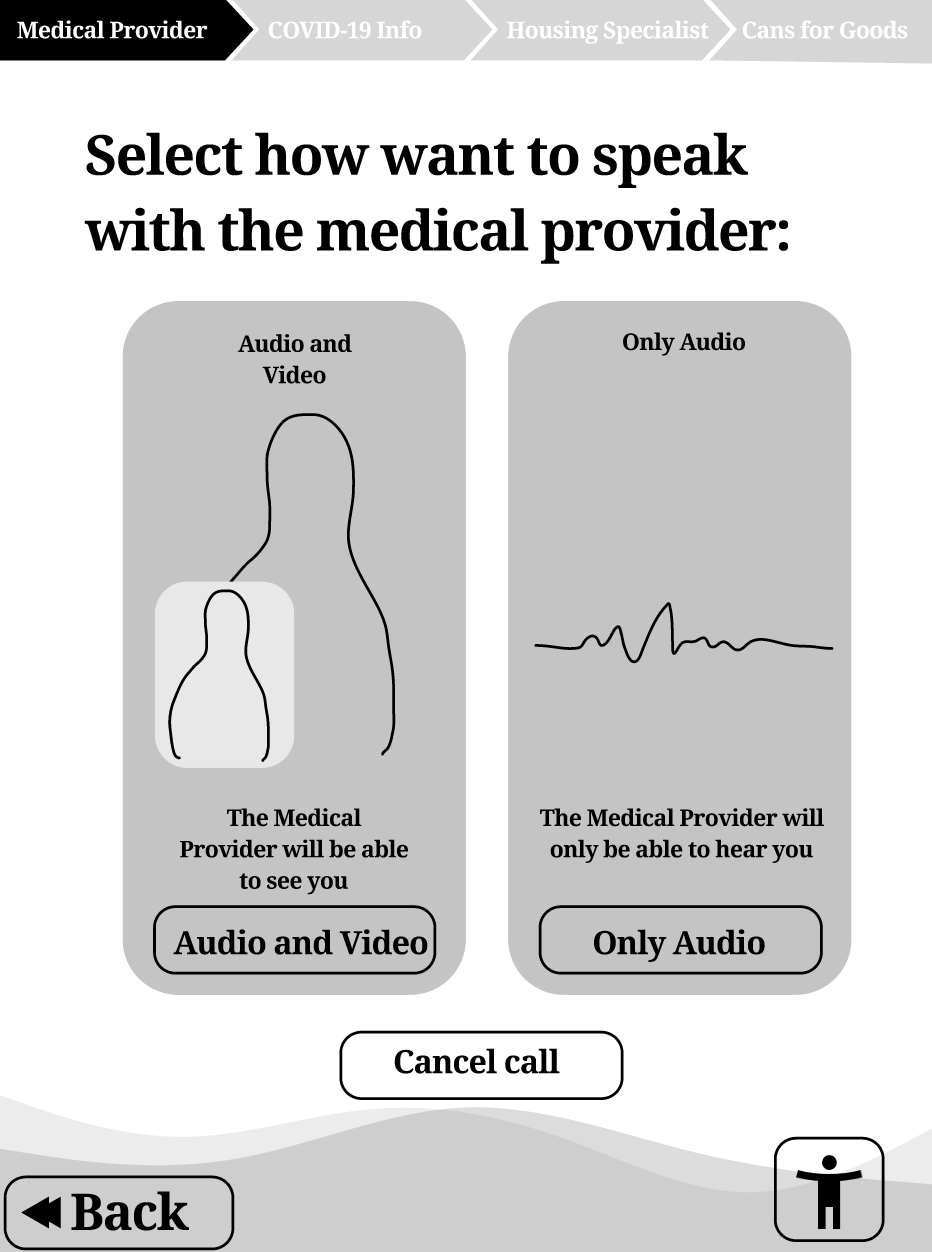

At this point in the design process, we were ready to build our first medium-fidelity prototype. In this prototype, we focused on the screen and not the physical aspect of the prototype. We aimed to gain feedback before we invested more time into creating a polished and comprehensive version of the machine. We also wanted to validate how we interpreted our user research and user needs in our design.

User Testing

We conducted moderated remote usability testing of our initial prototype. We tested the prototype in a group with four evaluators over Zoom. Evaluators are estimated to be between 20 to 35 years of age. All are students at the Human-Centered Design and Engineering Program (HCDE). While testing our Figma prototype, one person shared the screen while other evaluators watched and offered feedback.

Through testing, we received valuable feedback on the visual and interaction design of the prototype. We were able to make tweaks to several macro and micro elements of the design, including updating the language screen to make more sense for English as a Second Language (ESL) speakers and including page transitions to allow users more flexibility in task flow.

The high-fidelity prototype includes a user interface created in Figma and a rendering of someone using the carepoint vending machine. In this design, we focused on user privacy, accessibility and inclusion, navigation, and the learning aspects of the UI. We followed industry best practices and insights from our user research. Additionally, we wanted the physical pod to be transportable and accessible to people with disabilities, including wheelchair users.

The carepoint vending machine has these four functions:

- Connect PEH to healthcare providers

- Provide basic and up-to-date information related to relevant public health information

- Connect PEH to an existing resource

- Provide essential hygiene/items to PEH in exchange for empty bottles or cans

Challenges

Time and resources: Our team set out to create a complex design artifact in only 9 weeks. We all had varying levels of experience with research, design, and user testing. We had to learn quickly and complete portions of the project with laughably limited resources.

Scope: Our team started with a broad directive: to create a design solution that tackled raising the rate of COVID-19 vaccination, which is a large and complex topic. Even when we narrowed down to a specific user group (PEH in King County), the problem felt large and ill-defined. Our research helped us target a real issue (lack of trust), but throughout the project, we still struggled to keep our design artifact focused.

Ethics and equitability: Because our design’s target user group is such a vulnerable population, we were very wary of taking advantage of unhoused people for testing and research. We tried to approach each conversation with maximum sensitivity, which definitely threw up some roadblocks to research (we certainly weren’t “moving fast and breaking things,” to use a common tech term). If we had more time, we’d want to design an ethical research plan with people who interact closely with members of the unhoused community.

Final Thoughts

People experiencing homelessness face multiple seemingly insurmountable challenges every day. Homelessness is a complex issue (a “wicked problem,” even), and so is COVID-19 vaccination (both access and information). Through our research, the issue of trust and mistrust came up again and again. This is not an issue that will be solved by a single vending machine. However, also through our research, we learned the importance of individual interactions and the human touch. One of our overarching goals was to make sure PEH felt cared for and respected by a system that typically overlooks their wants and needs.

Carepoint attempts to tackle these wicked problems by providing resources and connections for a population that often flies under the radar of the housed community around them. With community buy-in, organizational support, and continuous user testing among the vulnerable population it is meant to serve, we believe that carepoint could be a vital tool in keeping people experiencing homelessness safe and healthy.